The Mistakes of the Past are Fast Creating a Crisis for Younger Americans

Lyman Stone Jun 24, 2019

Research fellow at the Institute for Family Studies

Carlina Teteris / Getty

The Baby Boomers ruined America. That sounds like a hyperbolic claim, but it’s one way to state what I found as I tried to solve a riddle. American society is going through a strange set of shifts: Even as cultural values are in rapid flux, political institutions seem frozen in time. The average U.S. state constitution is more than 100 years old. We are in the third-longest period without a constitutional amendment in American history: The longest such period ended in the Civil War. So what’s to blame for this institutional aging?

One possibility is simply that Americans got older. The average American was 32 years old in 2000, and 37 in 2018. The retiree share of the population is booming, while birth rates are plummeting. When a society gets older, its politics change. Older voters have different interests than younger voters: Cuts to retiree-focused benefits are scarier, while long-term problems such as excessive student debt, climate change, and low birth rates are more easily ignored.

But it’s not just aging. In a variety of different areas, the Baby Boom generation created, advanced, or preserved policies that made American institutions less dynamic. In a recent report for the American Enterprise Institute, I looked at issues including housing, work rules, higher education, law enforcement, and public budgeting, and found a consistent pattern: The political ascendancy of the Boomers brought with it tightening control and stricter regulation, making it harder to succeed in America. This lack of dynamism largely hasn’t hurt Boomers, but the mistakes of the past are fast becoming a crisis for younger Americans.

Zoning codes in America have their roots in the early 1900s. Some land-use rules arose out of efforts to manage growing density in cities due to industrialization and new construction technologies that allowed taller buildings. But most zoning was intended to protect property values for homeowners, or to exclude certain racial groups. For many decades, though, zoning codes were relatively limited in scope.

Stricter zoning rules began to be implemented in many places in the 1940s and 1950s as suburbanization began. But then things got worse in the 1960s to 1980s. This shift is reflected in the increasing frequency with which various land-use associated words were used in Google’s database of American English-language publications. These decades, when the political power of the Baby Boomer generation was rapidly rising, saw a sharp escalation in land-use rules.

There’s debate about why this is: Some researchers say the end of formal segregation may have pushed some voters to look for informal methods of enforcing segregation. Others suggest that a change in financial returns to different classes of investment caused homeowners to become more protective of their asset values.

Today, strict land-use rules—whether framed as rules about parking, green space, height limits, neighborhood aesthetics, or historic preservation—make new construction difficult. Even as the American population has doubled since the 1940s, it has gotten more and more legally challenging to build houses. The result is that younger Americans are locked out of suitable housing. And as I’ve argued previously, when young people have to rent or live in more crowded housing, they tend to postpone the major personal events marking transformation into settled adulthood, such as marriage and childbearing.

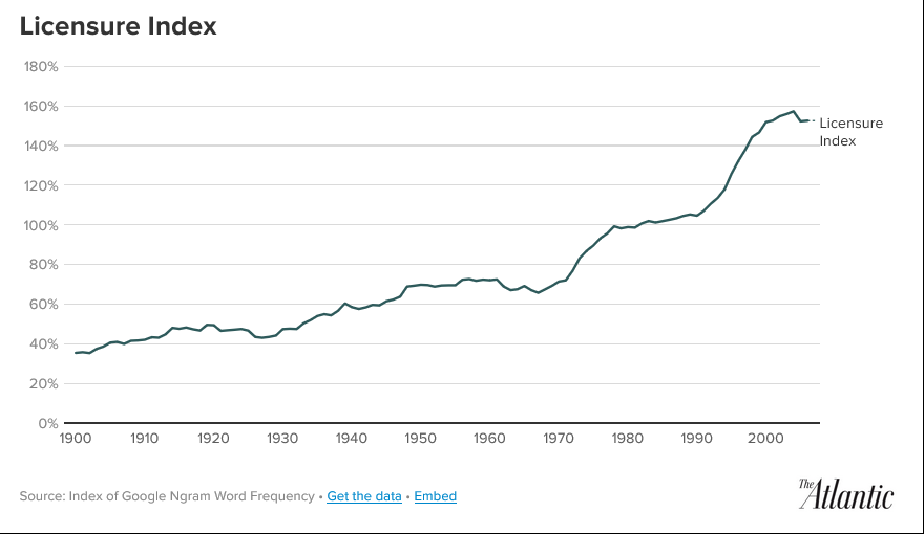

But, of course, Boomers didn’t only make rules that nudge young people out of homeownership. They also made new rules restricting young people’s employment. Laws and rules requiring workers to have special licenses, degrees, or certificates to work have proliferated over the past few decades. And while much of this rise came before Boomers were politically active, instead of reversing the trend, they extended it.

Just as tight land-use rules make existing homeowners richer by reducing how many new houses are listed on the market, strict licensing rules make existing workers richer by reducing competition in their fields. And while some industries clearly need licensing rules for health and safety reasons, most of the growth in licensure has been in fields where health and safety justifications are less salient: Do you really need hours of course work and special exams to be a florist, an interior designer, or an auctioneer?

By privileging existing workers, licensure rules increase income inequality, and they do so specifically by shifting income toward older workers. When licensure standards exclude felons, they also disproportionately affect minorities. Young people, and especially minorities, are increasingly being legally prohibited from work.

Again, scholars differ on explanations for why licensure has proliferated. It could be that work has simply gotten more complex. Or it could be that the decline of unions led to a search for new ways to maintain occupational closure. Increased gender and racial integration in workplaces may also have led to a search for new forms of hierarchy.

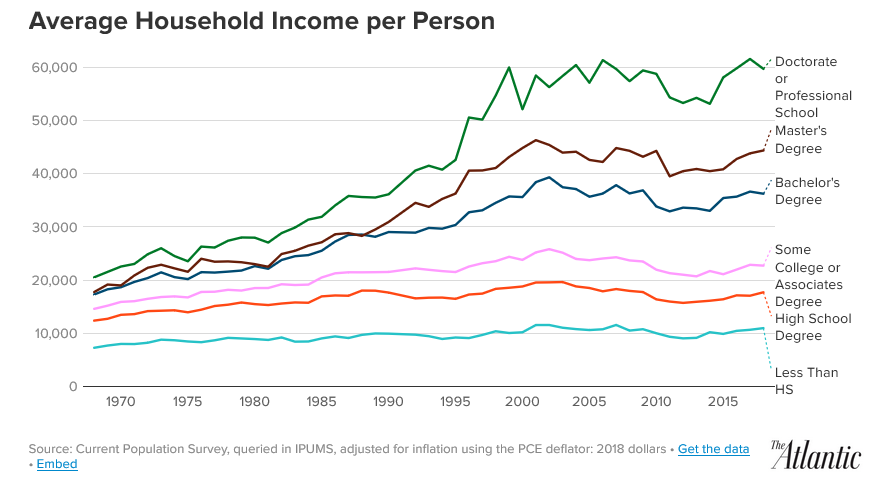

But even for workers who don’t need a formal license, barriers to work have grown over time. Jobs that once required a high-school degree now require a college degree. This escalation of credential requirements has created a kind of educational arms race. The rise in collegiate attainment, again, did not begin with Boomers. Rather, the GI Bill, and the explosion in new university chartering that it underwrote, created a new norm of college education for many jobs. With the rising availability of higher education, employers, who tend to be older than their employees, often demand degrees as licenses.

Meanwhile, even as higher education gets more expensive, the actual economic returns to a university degree are about flat. People who are more educated make more money than people with less education, but overall, most educational groups are just treading water. The social norm requiring degrees for virtually any middle-class job is one largely invented by Boomers and their parents, and enforced by those generations.

As with formal licensing and land-use rules, there are explanations for the rise of degree requirements: greater public support for education, a complex economy, growing demand for knowledge-workers. All probably have some validity. But the actual enforcement mechanism for this norm is explicitly generational: older employers setting standards for younger job applicants.

And whatever specific factors contributed to the rise of licensure, land-use rules, and demands for more degrees, these developments are part of a wider social trend toward increasing control and regulation across all walks of life. Regardless of changes in formal segregation, unionization, demand for knowledge workers, returns to various asset classes, or other explanations for the rise of work and housing regulation, what is striking is that these trends occurred simultaneously. A graph tracking the rise in paperwork needed to start a new business, or the length of census questionnaires, or the length of the federal code, or virtually any measure of administrative or regulatory complexity would show the same basic trend. Sector-specific explanations seem a bit suspect when the trend itself is so general.

The most glaring example of this growth in regulation and control is also the easiest one to pin on Baby Boomers: the incredible rise in incarceration rates. Even though murder rates are today at the same levels they were in the 1950s, the imprisoned share of the population is higher in America than in any country other than North Korea. We imprison a larger share of the population than authoritarian countries such as Turkmenistan and China.

That huge spike has a very clear origin in the crime wave of the 1960s and 1970s. Academic research has shown that incarcerating more criminals does reduce crime somewhat, so, as with all the other examples I’ve given, this response was understandable.

But many countries experienced a similar crime wave. Most of them experienced similar crime declines in the 1990s, even without so much imprisonment. Furthermore, research has also shown that imprisonment patterns in America were heavily biased by race, with incarceration rates not always reflecting actual rates of criminality.

Today, while incarceration rates are edging lower, they remain astonishingly high. Even as younger Americans are locked out of jobs and housing by strict rules set by previous generations, a startlingly large share of them, especially in minority communities, are literally behind bars. Those who remain free are nonetheless bereft of family, friends, and potential co-workers—and whole communities are, as a matter of law, stripped of potential workers.

It’s understandable that, faced with a wave of crime, Baby Boomers might want to respond with a law-enforcement crackdown. But the scale of the response was disproportionate. The rush to respond to a social ill with control, with extra rules and procedures, with the commanding power of the state, has been typical of American policy making in the postwar period, and especially since the 1970s. And whatever specific arguments may have justified a command-and-control response to crime, this kind of response reared its head for every major political problem encountered by Baby Boomers: housing, jobs, education, crime, and, of course, debt.

Even young Americans today who are free from prison are nonetheless in bondage to debt—sometimes their own debt, in the form of rapidly growing student loans or personal and credit-card loans. But on a larger scale, the problems of entitlements, pensions, Social Security, Medicare, and federal, state, and local debt are becoming more severe all the time. Already, in places such as Detroit, Illinois, and Puerto Rico, where political rules make flexible solutions hard and the population is aging very quickly, massive debt restructurings loom large. But around the country, the pressures of long-term obligations will grow.

Below, I show a reasonable projection of the share of national income that will have to be spent paying for these obligations in the future if there is no substantial restructuring of liabilities. It’s based on consensus forecasts from groups such as the Congressional Budget Office and the Office of Management and Budget for economic growth and for programs such as Social Security and Medicare where such forecasts are available—but in some cases, such as state debts and pensions, no such forecast was available, and so I developed a simple one.

Making these payments will require fiscal austerity, through either higher taxes or lower alternative spending. Younger Americans will bear the burdens of the Baby Boomer generation, whether in smaller take-home pay or more potholes and worse schools.

Furthermore, the basic demographic balance sheet is getting worse all the time, increasing the relative burden on young people. Working-age Americans are dying off in alarming numbers.

The odds of a 32-year-old dying have risen by 24 percent in the past five years, even as death rates among older Americans are about stable. Baby Boomers are living longer even as the workers who pay for their pensions are dying from an epidemic of drug overdose, suicide, car accidents, and violence. But, of course, while this sudden increase in working-age death rates is a new concern, the long-run fiscal crunch has been obvious for decades.

For virtually the entire period of Boomer political dominance, it has been obvious that long-term obligations needed to be fixed. And yet, the problem has not been fixed. Younger Americans will suffer the consequences.

As dire as this all sounds, there is cause for hope. If the problem is too many senseless rules, then the solution is obvious. Strict licensure standards can be repealed. Minimum lot sizes can be reduced. Building-height ceilings can be raised. Nonviolent prisoners can have their sentences commuted. Even thorny problems such as cost control in universities can be addressed through caps on non-instructional spending, while solutions for government debt and obligations are widely known, even if they are politically unpalatable.

Not all of these problems were first caused by the Boomers, but they each worsened on their watch. If leaders in business, education, and politics want to solve these problems, they can. Whether the gerontocracy in charge today wants solutions may be another question altogether.

O.K. BOOMER?